- News

- #ByInvitation: In the clash over pets: rights matter, so do rules

#ByInvitation: In the clash over pets: rights matter, so do rules

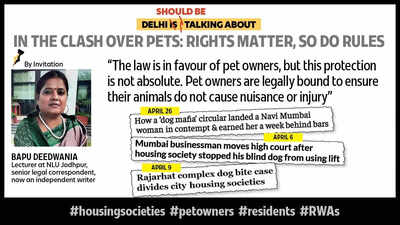

For this week's 'By Invitation', we have Bapu Deedwania, a lecturer at NLU Jodhpur and a senior legal correspondent, now an independent writer, who highlights growing tensions in urban India over pet rights, safety, and shared space regulations.

Recently, the Bombay High Court sentenced a woman to simple imprisonment for contempt of court. A resident of an upscale Navi Mumbai gated community, she had been part of a long-standing legal battle between residents, challenging the Animal Birth Control (ABC) Rules, 2023 — a law that mandates residential associations to accommodate the feeding of stray animals.

The woman’s offence stemmed from a circular she sent out, alleging that courts defend dog feeders and make a mockery of pet attack incidents, even referring to judges as being “part of a dog mafia.” Her apology was rejected, and she now finds herself alone in facing the judiciary’s wrath. Yet, the larger sentiment she voiced — of residents feeling vulnerable to pet-related incidents— cannot be dismissed outright. With pets increasingly seen as family members, shared spaces in gated communities are becoming flashpoints. While the law tends to protect pet owners, barking or the absence of immediate cleanliness are not sufficient reasons for eviction — conflicts inevitably arise. Take, for instance, the case of a Mumbai man who recently moved court after his pet dog was denied entry into all three elevators of his housing society.The society’s management cited hygiene and safety concerns, arguing that other residents were uncomfortable sharing elevators with animals.

The law, as it stands, leans heavily in favour of pet owners and animal lovers. According to rules and clarifications issued by the Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI), discrimination against pet owners is illegal. RWAs cannot ban pets from using elevators, parks, or common areas. Similarly, they cannot impose fines merely for keeping a pet. The Indian Constitution itself, under Article 51A(g), enshrines a duty to show compassion to all living creatures, reinforcing the protection extended to pets and stray animals alike.However, this protection is not absolute. Pet owners are legally bound to ensure their animals do not cause nuisance, injury, or intimidation to other residents. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 and local municipal laws further mandate proper leashing, vaccination, and sanitation protocols. If a pet repeatedly attacks or causes harm, societies can seek specific prohibitory injunctions through courts, balancing the rights of all. Lawyers from the Bombay High Court note that while animal rights are protected, the absence of a clear-cut, dedicated pet ownership law creates grey zones. Safety concerns are real. Especially when certain breeds — bred for guarding or hunting — are kept in densely populated residential settings, the risks cannot be overlooked. Experts warn that a running child or a vulnerable senior can easily become an unintended target, with tragic consequences.

To mitigate conflict, experts suggest proactive dialogue between RWAs, pet owners and other residents, before moving in. Setting up pet play zones with picket fencing, designated walking times, compulsory leashing in common areas, and structured waste disposal systems are increasingly being adopted as best practices. Crucially, some boundaries are non-negotiable — swimming pools and children’s play areas, for instance, are often deemed pet-free zones.As urban India continues to embrace pets while living in increasingly vertical, shared spaces, the flashpoints between pet owners and other residents are only set to rise. The law offers protection, but it also demands responsibility.

End of Article

Follow Us On Social Media