- News

- Protest playlist: Nepal’s musicians navigate chants, politics on stage

Protest playlist: Nepal’s musicians navigate chants, politics on stage

Across Nepal and its diaspora, a wave of discontent simmers, expressed through music and art. What began as nostalgia for the monarchy is evolving into anti-government sentiment, particularly among the youth.

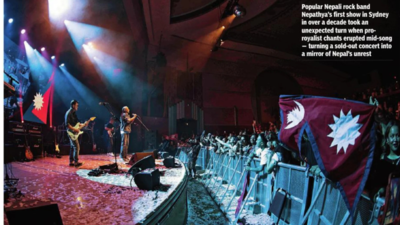

Kathmandu : The drums kick in first — slow and steady, under a cascade of guitar riffs and a familiar hum of thousands waiting for a cue. At Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion on March 29, Nepathya is on stage, and for a moment, it’s only music. And then it happens — from the crowd, low first and then louder: “Raja aau, desh bachau (Return, king, to save the country).”

The chant doesn’t start with the band. It doesn’t even come between songs. It happens mid-verse, like an aftershock of a memory the crowd didn’t know it carried. What began as nostalgia was morphing, mid-chorus, into full-throated anti-govt slogans. The timing is not lost on anyone. Just a day earlier, two people were killed in clashes during a pro-monarchy rally back home in Kathmandu.

Amrit Gurung, 57, looks up from the mic. The band doesn’t stop, but something in the air shifts — a pulse that can’t be un-felt. It wasn’t an isolated moment. It was something else: a loud beep in the soundtrack of the republic.

Later, Nepathya issued a cautiosly worded statement. “We didn’t expect that kind of outburst. We are musicians, not political agents.” But by then, the clip was already online — layered with old footage of former king Gyanendra Shah waving to crowds, complete with hashtags about betrayal and belonging.

The moment gained traction partly because of where it happened. Australia is home to one of the largest and fastestgrowing Nepali diasporas — over 1.3 lakh people of Nepali origin were living in Australia as of 2023, according to the country’s department of home affairs. The bulk arrived post-2006. Monarchy was formally abolished in 2008, and the country almost immediately found itself grappling with democratic instability.

Across Nepal and its diaspora, something is stirring. In concert halls, live music venues, and open-mic events, the symbols of monarchy are bleeding back into the culture, not through manifesto but music.

In Kathmandu, 21-year-old Sarita Bhandari is revising for a biomedical exam while scrolling through her phone. The Sydney concert video pops up again, in different filters. “We’re tired. We sing about change.”

That restlessness — unclaimed and urgent — is everywhere in Nepal’s youth culture. It thrums through US-based rapper VTEN’s (Samir Ghising, 28) ‘Boka’, which exploded in 2022, and in Uniq Poet’s (Utsaha Joshi, 31) ‘Ma naramro manche’, a quiet rebellion in verse. These songs don’t mention kings or constitutions. They’re not monarchist, but they are blistering in tone, simmering in message.

And then there’s ‘Lutna sake lut’ (Loot, if you can), the satirical folk track by Pashupati Sharma, 42, that was briefly pulled off YouTube in 2019 after alleged threats from the ruling party’s youth wing. Songs like Sharma’s were among the most streamed Nepali folk tracks that year on YouTube. “My intention was never to of-fend anyone,” Sharma told TOI. “But we can’t close our eyes to what the people of the country are going through.”

Necessity and reinvention

Even Deep Shrestha — the 74-year-old softspoken pioneer of Nepali pop, whose 1981 ballad ‘Jhaskiyechha maan mero’ captured a generation’s quiet ache — sees the turn in the wind. “In our time, we sang to reach people’s hearts,” he said. “Today, the heart and the street have become one.”

But not every song now echoing in protest is meant as protest. Some are being co-opted, recast, distorted. The nationalist anthem ‘Rato ra chandra surya’ (Red, moon and sun — the colours and symbols on the Nepal flag), originally written dur-ing the Panchayat era, a partyless political system under absolute monarchy from 1960 to 1990, was meant to evoke national unity and loyalty to the crown. Today, it’s finding new life in TikTok videos that mock or mourn the present.

“We used to sing this during school assemblies,” says 25-year-old designer Aashish Khatri. “Now we remix it when the internet’s down or when the PM says something dumb. It’s a cultural side-eye.”

Poet and playwright Manjul, who has worked with musicians across party lines, said people are interpreting lyrics the way that suits them: “It’s a mirror. What you see in it says more about you than about the artiste.”

For women artistes, the tension cuts deeper. Jerusha Rai, 34, a London-born indie singer whose 2016 album ‘Sunsaan’ (Silence) was praised for its take on identity, says the pressure to sound patriotic is always lurking. “There’s a quiet demand to pick a side,” she says. “But sometimes, just surviving the noise is its own act of protest.”

Nepathya’s ‘Dhoka’ (Door), released in 2023, wasn’t political at all. It was a song about heartbreak. When the band played it in Pokhara last year, the crowd again shouted royalist slogans mid-set. “We paused,” bassist Shreyas said later. “We don’t stop people from expressing. But we also didn’t write that song for any king.”

That tension — between intention and reception — runs like a fault line through Nepal’s creative landscape.

Nearly 5 lakh Nepalese citizens left the country in 2023 to seek foreign employment, according to Nepal’s department of foreign employment. For many young Nepalese, the longing may be less for monarchy and more for the dignity of a future for which they don’t have to leave home.

Beyond the mic

It’s not just in music that Nepal’s restlessness shows. In Kathmandu’s alleys and underpasses, images are surfacing — crowns cracking under lightning bolts, saffron flags melting into spray-painted nooses, caricatures of political leaders. One wall near Tripureshwor is scrawled with the words ‘Desh lai raja chahinchha?’ (‘Does the country need a king?’) in looping letters that spiral into a broken rupee symbol.

The mural was painted by a street art crew called Hamro Rang (‘Our Colour’), which describes itself as non-partisan but not apolitical. “We’re not saying bring the king back,” says Prabin, one of its founders. “We’re asking why people think that’s the only option left.”

These questions are echoing far beyond Kathmandu. In Janakpur, a southern border town steeped in Mithila culture, a community theatre group has begun weaving anti-corruption songs into folk dramas. In Baglung, a western hill district, teenage girls record TikTok videos set to monarchy era songs, layered with sarcastic captions like ‘Back to the future?’ In Dharan, an eastern town near the Indian border, college students held an open mic titled ‘Chaotic Republic’, ending with a dance piece.

Not all artists welcome the remix. In Jhamsikhel, a Kathmandu neighbourhood, a mural of a crown above barbed wire triggered online outrage. The artist, Siro, explains: “It was meant to show entrapment, not endorsement. But everyone saw what they wanted.”

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA