- News

- entertainment

- bengali

- movies

- Is making a politically meaningful film in this country even worth it?: MS Sathyu

Trending

This story is from February 2, 2019

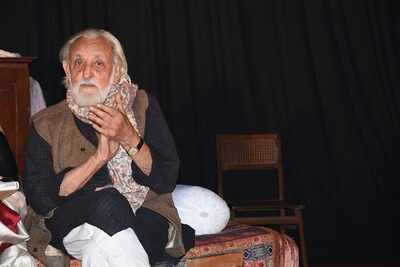

Is making a politically meaningful film in this country even worth it?: MS Sathyu

A walk down memory lane

During his stay, the octogenarian filmmaker and theatre personality took a stroll around Nandan and visited the Tollygunge studios. He also paid a visit to his ailing friends — photographer Nemai Ghosh and cinematographer Soumendu Roy. “They are younger to me,” said Sathyu as he spoke of the fragile health of his old companions, who are also in their 80s.

The undying spirit

Blaming the multiplex culture

Sathyu puts a part of the blame for such a scenario on the multiplex system. “At multiplexes, monetary merit is the sole criterion to decide on the exhibition of a film. This attitude of thinking only about the hundreds of crores made in a given week is wrong. You need to talk about the story, the performance and the director’s vision. This situation has led to more money being spent on a film’s marketing than its making,” Sathyu explained with a glint of irony.

The Bengal connect

Unafraid and uncompromising in upholding his artistic ideals, Sathyu still embodies the qualities that made him one of the most political storytellers in the country. It also makes him choose Mrinal Sen, from amongst Bengal’s holy trinity of filmmaking, as the one he feels himself closer to as a filmmaker.

“Ritwik Ghatak was a mad genius whom we lost too early. Satyajit Ray, having been an ad filmmaker, was more sophisticated and analytically perfect. But Mrinal Sen, in my opinion, was a kind of poet whose work was more lyrical and spontaneous,” he said, remembering the film maestro who recently passed away, adding, “He also gave Indian film language something new with films like Bhuvan Shome.”

On today’s actors

A member of the socialist Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) just like Sen, Sathyu still considers honesty and idealism to be the cornerstone of an artiste and is appalled “by the lack of it in actors today”. “Nawazuddin Siddiqui does Manto and being a good actor, he manages to get it done. But then he does Thackeray. Does he have nothing to say as an artiste? Then you have Anupam Kher, who says he has done the most difficult role of his life as Manmohan Singh in The Accidental Prime Minister. How can that be more difficult than doing a Saaransh?” he questioned. He is also critical of a string of recent releases ahead of the 2019 elections. “The Indian Army has always conducted surgical strikes. So why do you choose to make a film like Uri: The Surgical Strike only now?” asked the filmmaker.no acting aspirations. He also has no qualms about questioning the dedication of top actors to their craft when they spend more time endorsing products than perfecting their art. Incidentally, in 2013, Sathyu acted in an advertisement for a global search engine that went viral on social media and brought with it “the nuisance of being continuously offered inane acting roles”. Made by Badhaai Ho (2018) director Amit Sharma, the commercial — Reunion — told the story of two friends who are separated by Partition but helped by technology to find each other. “I don’t have any ambitions as an actor. I took the project up as it was a sensitive story of friendship between the two countries. In the process, I was paid the kind of money that I have never earned in my life. Since then, I keep getting acting offers that I have to keep refusing. They offered me to do something for PM Narendra Modi and even endorse a paan masala brand. I might have made ads for cigarettes in my youth, when I was trying to earn a living and was less aware, but I wouldn’t do those jobs now,” said Sathyu while lamenting the lack of such integrity in today’s actors.

The transition of cinema

With more than 50 years having passed since his first film assignment as the art director for Chetan Anand’s Haqeeqat (1964), Sathyu has witnessed the transition of cinema from film to digital. While he welcomes the new avenues that technological innovations have opened for filmmakers, he is not convinced by the change in film language and content that these advancements have brought along. “It is good that you can showcase your work not just in a theatre but even on a smartphone. But it also restricts the scope of a film. When one uses a headphone to watch a movie, the sound gets constricted and it’s not heard at the intended level. But sound can create a certain impact on the audience at a certain level. Hence, the desired content of the film gets affected as does the grammar of the medium. Again, the larger-than-life quality of cinema is lost when one watches it on the mobile or even on the TV,” the filmmaker contended.

Concerns over political atmosphere

It is not just the rapid changes in the medium but also the political atmosphere in the country that worries the craftsman. “It all makes one a bit cynical. I wonder if it’s worth doing a politically meaningful film in this country anymore,” he remarked. But then, unlike the grim reality of the works of his favourite Mrinal Sen, Sathyu’s works reflect the subtle

optimism that one often sees in the endings of even the most sombre of Ritwik Ghatak’s films. “But then you say to yourself, your job is to do what you want to do and be totally honest about it. And continue doing so with the belief that things will change and that the new generation will want it to change,” he signed off.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA