- News

- India News

- Times Evoke News

- ‘Humans have created a new epoch on Earth — its markers include plutonium to chicken’

Trending

This story is from July 29, 2023

‘Humans have created a new epoch on Earth — its markers include plutonium to chicken’

Colin Neil Waters, geologist and honorary professor at the University of Leicester, is Chair of the Anthropocene Working Group. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, he discusses the drivers of a new planetary era:

What is the core of your research?

Our group has been investigating whether the Anthropocene should be included on the geological timescale of Earth — this means recognising that humans have had such an impact on the planet, we’ve changed it to the extent of starting a new epoch. The present geologic time is called the Holocene which started 11,700 years ago after the last glaciation. Human civilisation expanded slowly across Earth then. However, from the mid-20th century onwards, human impacts have been so dramatic, there has been a very sudden change between that world of the Holocene to what we are living in now.

To define units in geologic time, we study significant changes, examining sedimentary successions in lakes, oceans, corals, cave deposits, even glacial ice — these all have a record of what happened to the planet through time. We’ve been looking at 12 sites worldwide and recognised numerous changes — these include the presence of novel materials like plastics, changes to Earth’s chemistry and atmosphere, including increasing greenhouse gases, pollution and altered planetary biology with the loss of species and transfers of these across regions. All of these are encompassed in the concept of the Anthropocene. We’ve now selected one site called the Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) or the ‘Golden Spike’ — in that core, we can place the exact boundary where the transition between the Holocene and Anthropocene happens, using this as a global reference. We’ve announced Crawford Lake in Canada as our candidate GSSP.

What does Crawford Lake show us about Earth’s history and human impacts on it?

The core of sediments from there has a history going back around 1,000 years. It has an annual increment of growth or layering which is like tree rings, with variations — these indicate changes in chemistry, species, pollen from trees, etc., showing how the environment altered over time. Initially, there were signs of indigenous North American populations developing agriculture the 1300s onwards there. The colonial phase saw further agricultural developments. But these were local signs of change. From the 1950s, you start seeing a global signal with pollution like mercury and lead from heavy industry, altered nitrogen — there was a doubling of nitrogen across Earth in the 20th century, driven largely by fossil fuels and nitrogen-based fertilisers — causing different species to emerge alongside diseases like Dutch Elm which ravaged the area in the 1950s. But the key marker — importantly, this was present across all 12 sites — was the appearance of plutonium. This comes from the detonation of nuclear weapons in the 1940s and 1950s, spreading radioactive materials across Earth, this plutonium spike becoming a massive global signal. Burning fossil fuels increased carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere and produced small particulates, changing Earth’s chemistry — these have even been found in the Antarctic’s ice core.

Are there other Anthropocene markers?

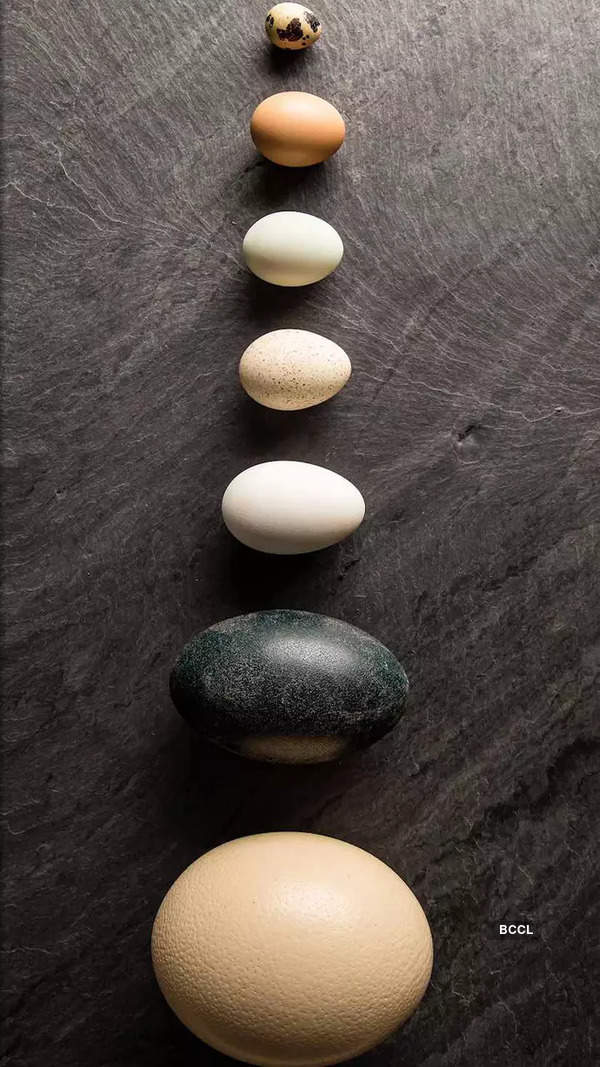

Plastic is a novel material herein — most polymers were invented around the 1940s, rapidly becoming part of our lives. Alongside rivers and oceans, microplastics are even in the atmosphere now. From the 1950s, there was also a large change in the biology of domesticated species, embodied in the broiler chicken — compared to the red jungle fowl, the modern chicken bred for consumption has bone sizes which are twice as big and body mass five times greater. This happened rapidly since the 1950s, with this changed chicken looking practically like a new species. Chickens are the most abundant bird on Earth now and could be the fossil marker of the Anthropocene.

BEYOND BEAUTY: Eucalyptus (above) and lantana (below) are invasive species humans moved (Picture: iStock)

Most of these changes emerged from the West — what does this indicate about climate justice?

By the 1950s, the signals of human impacts had become truly global. Originally, Paul J. Crutzen, the Nobel Prizewinning meteorologist, felt the Anthropocene should be dated to the Industrial Revolution. But when we looked at evidence of changes that happened then, these were much more in Europe and North America and spread slowly. However, after WWII, the transitions impacted all countries. Greenhouse gases are a global issue now — historically, Western countries emitted much of these. But by volume today, countries like China are the biggest emitters. Total emissions are more globally spread — so are impacts on temperature, etc.

Is an understanding of human impacts central to environmental action?

Many impacts initiated in the mid20th century started without much knowledge. Information about what fossil fuels or plastics do is widespread now. Scientists show us these effects with real-time monitoring. Hence, it’s easier to make political decisions today about how to proceed — should we keep emitting like this or find alternatives? In the 1950s, a global population of 2.5 billion people dramatically changed Earth’s environment — if eight billion people were collectively determined, they could have a big impact on correcting our footprint. Once, lead in gasoline was common but with information, it became widely banned, reducing it in the atmosphere. We can have a significant impact quickly — if we know we have an issue.

Stay updated with the latest India news, weather forecast for major cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Noida, and Bengaluru on Times of India.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA