- News

- India News

- Times Evoke News

- 'Our 505-million-year-old jellyfish fossil finds show how life began and Earth transformed'

Trending

This story is from August 5, 2023

'Our 505-million-year-old jellyfish fossil finds show how life began and Earth transformed'

Palaeontologist Jean-Bernard Caron is associate professor of earth sciences at the University of Toronto. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, he discusses his remarkable discovery of ancient jellyfish:

What is the core of your research?

I work on jellyfish fossils that date back millions of years. We know of jellyfish today in modern oceans — some people may have received stings because of their tentacles which are designed to grab prey. Tentacles define this group of beings called cniadarians which includes corals. I study this and work as curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM).

Why is it important to study the history of these invertebrates?

A DAY AT WORK: Experts search for fossils at the Burgess Shale fieldwork site. Photo: Desmond Collins ©Royal Ontario Museum

Please tell us about your new discovery of a 505-million-year-old jellyfish fossil?

We found this on mountains in the Canadian Rockies in British Columbia. The site is called Burgess Shale where such fossils were earlier found by Desmond Collins of the ROM. It became a World Heritage Site in the early 1980s, famous for the exceptional preservation of soft-bodied fossils. That means fossils which don’t have shells or bones and typically don’t get preserved. Here, the discovery of these jellyfish remnants, now called Burgessomedusa phasmiformis, brings the fossil record to a new high in terms of what can be preserved — considering that jellyfish are 95% water, these fossils are exceptional.

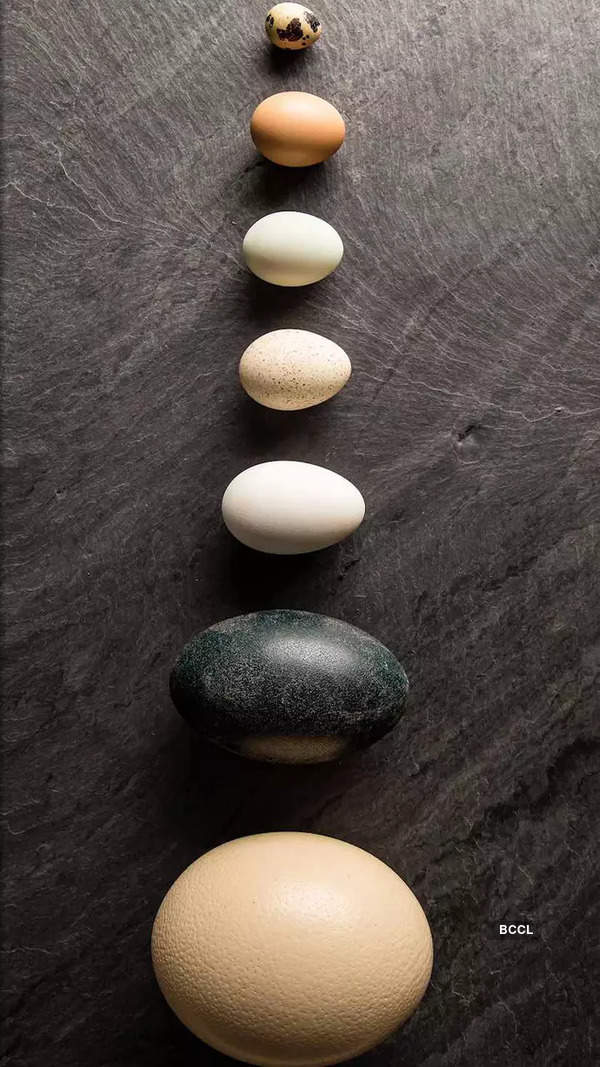

ONCE A SEA: The 505-million-year-old marine jellyfish fossils (Below) are in rocks in the Burgess Shale mountains (Above). Photos: Desmond Collins ©Royal Ontario Museum, Via: Jean-Bernand Caron

What do these tell us about evolutionary drivers like food webs or the rise of animals which could swim?

From the context of a Cambrian animal, these jellyfish or medusozoans are really large. Most fossils with shells are no larger than a human finger but these are the size of a forearm and have their tentacles preserved. It is very rare to find fossils of beings which swam in that environment — but clearly, swimming was a well-established behaviour for many animals like Anomalocaris, a giant predator related to anthropods. Understanding that entire food web is important. Free-swimming jellyfish were a crucial part of it, eating anthropods and other organisms, controlling species and growing larger, developing a bell-shaped form.

Do they show us how life on land began?

At the time, all animal life actually lived in the oceans. The origin of life itself is much older — it started with very simple cells, maybe four billion years ago. It took 3.5 billion years to start more complex life forms. It’s only relatively recently that animals evolved during the so-called Cambrian Explosion around 541 million years ago.

The group which includes jellyfish evolved not more than 600 million years ago, whereas life on land, especially animals, happened much later, perhaps 450 million years ago. The first animals on land were likely anthropods or species with jointed limbs like shrimps, lobsters, etc. It is only much later that vertebrates made it on land.

The Burgess Shale itself gives us a glimpse of life 505 million years ago — it shows us representations of most of the modern groups of animals we know today, including ourselves. Many look quite different but share characteristics we still find — for example, in our ancestors who are much younger than jellyfish, we find a lumbar cord which becomes the vertebrae in ourselves. As these remnants indicate, a diverse community lived back then and the jellyfish was an important member of it, a f a c t w h i c h remained undiscovered for a long time. We are happy to be able to publish our findings of it now.

A CAMBRIAN LIFE: An artistic version of Burgessomedusa phasmiformis. Art: Christian McCal

Your discovery also indicates the Burgess Shale mountains must once have been a sea — what do these fossils tell us about the evolution of landscapes on Earth?

That is fascinating because we found these marine fossils at 250 to 300 metres elevation in these mountains whereas in the Cambrian time, they were in the ocean at 100-metre depth. This shows us the process of plate tectonics — part of Earth is made of plates which move against each other. At times, they collide, a process which made the Rockies, or go under continents and push up, like the Himalayas in the Indian subcontinent.

We are living on a dynamic planet — the fossils we have found now on top of these mountains have a magical aspect to them. When you think about where these beings actually lived, you realise how much has changed — and how landscapes have completely transformed.

Stay updated with the latest India news, weather forecast for major cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Noida, and Bengaluru on Times of India.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA