- News

- India News

- Times Evoke News

- ‘The Anthropocene has colonial roots — its technological leaders gained from empires like India’

Trending

This story is from July 29, 2023

‘The Anthropocene has colonial roots — its technological leaders gained from empires like India’

Mahesh Rangarajan is professor of history and environmental studies at Ashoka University. Speaking to Times Evoke, he discusses the complex colonial past — and a possible future of equity — shaping the Anthropocene:

The Anthropocene refers to a period of accelerated — and, to some extent, irreversible — changes in the ecosphere. In this, human actions have a central impact. Paul Crutzen first used the term for the period from the 1780s, coterminous with the Industrial Revolution in Europe (principally the United Kingdom) which was powered largely by fossil fuels, coal, oil and gas. Their combustion caused changes in green- house gases in Earth’s atmosphere, CO2 being only one here.

The other definition used by historians, particularly John Mc- Neill, has been applied to the period after 1945 — this has seen far-reaching transformations on Earth, much greater than anything in previous history. This includes the use of fossil fuels but also biodiver- sity loss, oceanic ecosystem change, an altered nitrogen cycle, etc. Importantly, these different trans- formations interact with each other — they are not to be viewed in iso- lation. There are different notions of the Anthropocene — but a commonality between them is that all these changes have a global, regional and local dimension.

It is also understood that the drivers of this epoch are not uniform — not all human societies everywhere have the same impacts. But the Anthropocene draws attention to how even a few who are burning fossil fuels or extracting minerals, transmitting compounds through the biosphere, have consequences for everyone on Earth.

Geologists have now dated the Anthropocene as starting in 1950. However, we cannot understand this view of the ecosphere without understanding the ‘technosphere’ or the technologies used by humans. Mid-20th century onwards, the impacts of these technologies were magnified — and the leaders of these were countries which had colonial empires earlier. Much of the Industrial Revolution was also about cotton, grown in India, Egypt and the Americas, mostly using slave labour in the US South. Cotton created wealth in England because of its overseas markets acquired often through force and de-industrialising Asia. So, 1950 has very deep roots.

This past and climate justice today are entirely related. The world has a vast number of people who lack adequate access to energy from nutrition, cooling, heating or basic transport. We cannot freeze at these levels of development. But the manner in which energy, fossil fuels and other resources are extracted and used to create more power reflects how a disproportionately small number of people have a much larger environmental footprint — consider the 10 richest countries versus the 50 poorest.

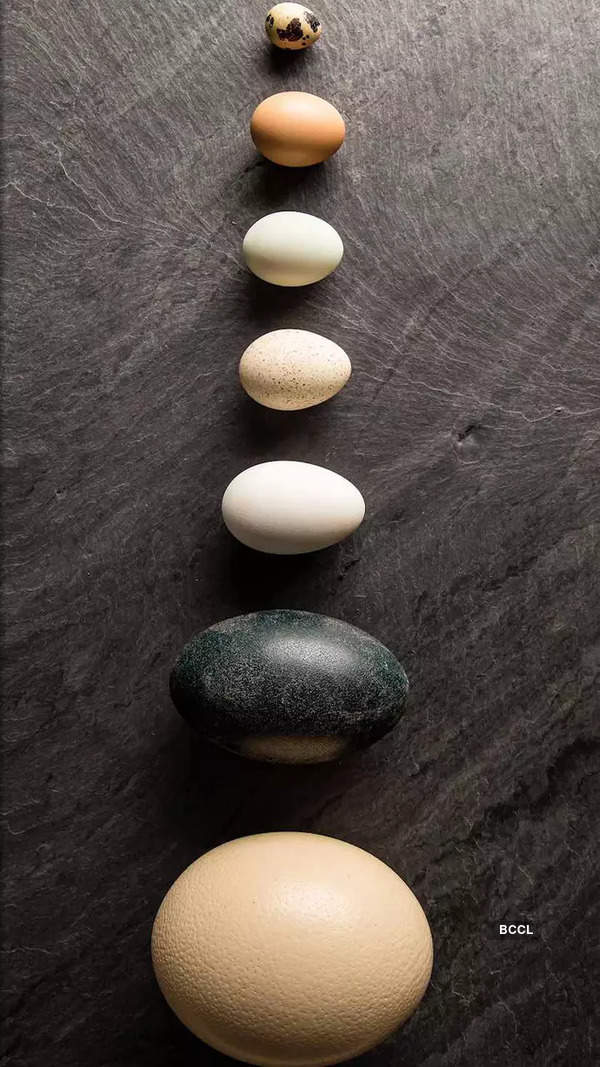

NOT A SOFT TALE: A bud of cotton holds stories of empire and slavery. (Photo courtesy: iStock)

This is not an argument for bringing all to the same base but the Anthropocene demands we phase out these extreme forms of energy inequality. We need wiser forms of energy and far more equity by privileging public transport over private, the targeted use of fertilisers instead of broadcast modes and renewable energy with minimal impacts on ecosystems and marginalised communities. Climate justice must go with the move to a greener model that keeps Earth safe, habitable and productive.

The Anthropocene also changed the equation between humans and other beings. The ecological writer, Barry Commoner, argued the technological revolution made people forget basic principles of ecology, such as all things being interconnected. Even flows of nitrogen and carbon need life systems to function birds, fish, insects, etc., are all part of those cycles. Commoner argued nature knows best and its species evolved in consonance with its principles of life. The biosphere the thin film of life which covers the planet and holds everything that lives interlinks all organ- isms and the material substances around them. Humans have transformed many of these substances. It requires maturity to recognise this now. The way we conduct our activities has consequences — Boris Pasternak, the Nobel Prize awarded Russian writer, said we should think of the consequences of such consequences. Establishing such thought is crucial to how we will relate to humans and other animals in the Anthropocene.

Stay updated with the latest India news, weather forecast for major cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Noida, and Bengaluru on Times of India.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA